I couldn’t believe my eyes the first time I saw the sign. At the Creswell exit from northbound 1-5, a new sign, installed when the marathon freeway overpass project concluded a couple of years ago, motorists are led to believe that if they turn right they will find their way to Cloverdale. What were the signs erectors thinking?

Historical information about Cloverdale is scant, and nearly all written word is a variation of A. G. Walling’s 1884 book called Illustrated History of Lane County. According to Walling, in 1851, E. P. Castleman built one of Lane County’s first sawmills on Bear Creek; its primary purpose was to saw lumber for the construction of a gristmill.

The gristmill, built by William Jones, and a general store operated by Jones and John Gilfry were the beginnings of Cloverdale, a few miles east of Creswell. Jones platted the town site of Cloverdale in 1855 and was duly recorded in the office of the county recorder. When Gilfry acquired the land from Jones several years later, Gilfry had the plat cancelled.

According to the December 1956 edition of the Lane County Historian, the Cascade Academy at Cloverdale was opened in 1853 and was the first institution of higher learning in Lane County, taught by Martin Blanding, a Yale University graduate. Blanding, considered by some historians to be the “poster boy” of the 1853 Lost Wagon Train, went on to become Lane County’s first school superintendent.

Seventeen-year-old Blanding, the first member of the party to be rescued, brought word of the emigrants’ plight. A great deal has been written about Blanding’s heroics, but I cannot help but wonder if there is an error in Blanding’s reported age — it’s hard to imagine someone becoming a university graduate and teacher and then traveling across the United States by age seventeen.

A search on Ancestry.com shows a death record for a 40-year-old male named Martin Blanding of Lane County, Oregon, who died in March 1870 of consumption. The death record lists Pennsylvania as his birthplace, and the original 1850 Federal Census document lists a 20-year-old Martin Blanding who was born in and living in Pennsylvania working as a farmer. His time and manner of death match other historical listings for Martin Blanding. If this were the same person, he would have been 23 in 1853, which makes this more plausible in regard to age.

John Whiteaker, who served as Oregon’s first governor, lived on a farm in the Cloverdale area after arriving in Oregon by way of the California Gold Rush. One of his accomplishments as governor was introducing legislation to settle numerous claims and counterclaims on public land and protecting land rights of legitimate settlers. Whiteaker later served in the U. S. Congress. He moved to Eugene in 1890 and purchased ten city blocks of the downtown area that is known today as the Whiteaker neighborhood.

Cloverdale’s claim to be a community isn’t bolstered by the U. S. Post Office. Thorough searches of Oregon Post Offices, a 1982 book by Richard Helbock; Oregon Postmarks — A Catalog of 19th Century Usage by Charles Whittlesey and Richard Helbock; and Postmaster Appointments for the State and Territory of Oregon 1847-1971 published by Oregon Territorial Press in 1998 show no listings for Cloverdale in Lane County. An additional check with a U. S. Postal Service historian yielded the same result. It wasn’t the lack of postal facilities, but instead construction of the Oregon and California Railroad in 1871 that was the beginning of the end of Cloverdale.

The railroad followed the established route of the Wells Fargo Stagecoach line, which was across the Coast Fork of the Willamette River several miles to the west. With the arrival of the railroad, Gilfry closed his Cloverdale store and moved it to the new rail stop, named for Postmaster General John Creswell, and Cloverdale as a business center all but disappeared.

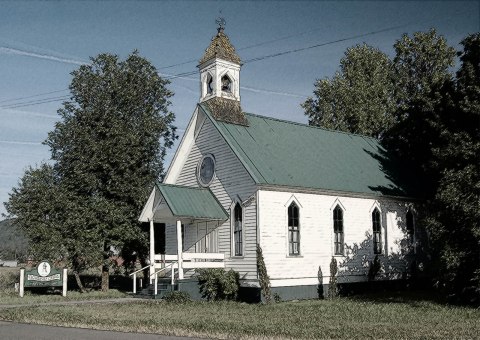

Today, the Cloverdale Chapel and Meetinghouse, the former Methodist/Episcopal Church built near the turn of the 20th century, keeps the Cloverdale name alive. The nearby Cloverdale Community Cemetery on Bradford Road keeps alive the memory of several of the earliest residents of this area. What Cloverdale was lacking – status as a post office – was about the only thing that Coast Fork had.

Today, the Cloverdale Chapel and Meetinghouse, the former Methodist/Episcopal Church built near the turn of the 20th century, keeps the Cloverdale name alive. The nearby Cloverdale Community Cemetery on Bradford Road keeps alive the memory of several of the earliest residents of this area. What Cloverdale was lacking – status as a post office – was about the only thing that Coast Fork had.

A blacksmith shop, trading post and a stop on the Wells Fargo Stagecoach line several miles south of present-day Creswell, the Coast Fork Post Office was established on Dec. 28, 1867 with George Rinehart serving as its first and only postmaster until the office closed on Oct. 1, 1872.

Establishing the Coast Fork Post Office’s former location has been challenging at best. Frances Quinn wrote an excellent book in the about the history of the Walker area. In that book she identifies the location of Coast Fork as 81618 Davisson Road; the “big red barn” is a recognizable landmark. Quinn also mentions that the location was also called the ‘Chrisman place’ — named in recognition of the original Campbell Chrisman donation land claim.

A little digging on the Internet unearthed some interesting results. One site, geody.com, which provides aerial photos and maps, shows the location of the Historical Coast Fork Post Office in a slightly different location. The aerial photograph designates a spot about a mile south of the Davisson Road marked by Quinn, across the railroad tracks “almost due east of the southernmost hangar at the Walker Airport.”

An examination of a donation land claim map shows the northern border of the Chrisman claim very close to the location shown on the Website. It is not known whether Rinehart operated the post office on property he acquired from Chrisman or on land still owned by Chrisman. What is known is that either location is near the namesake of the short-lived postal facility, the Coast Fork of the Willamette River.

Adding to the location confusion is the entry in Lewis A. McArthur’s third edition of Oregon Geographic Names, which reads in part when on describing Coast Fork, “Local tradition is to the effect that the post office was a little east of the present site of Creswell.” That information is in direct contradiction with all other information available about Coast Fork.

Since its beginning, the Postal Service has traditionally kept records about locations of the its offices, yet no records about the Coast Fork facility exist today, perhaps due in part to the nomadic nature of some remote offices that were maintained in private homes. The area served by Coast Fork Post Office is unknown, but one can reasonably assume it was in the area that now includes Creswell, because the Creswell Post Office wasn’t opened until March 1872, probably leading to the closure of Coast Fork.

To the south, Walker Post Office wasn’t opened until 1891, and the facility at Saginaw location didn’t open until 1898, so that area may have been included as well. The 1870 Federal Census lists 835 men, women and children calling Coast Fork their home and, for those who had been granted the right, voting precinct, including several families named Rinehart.

Our local area has a rich, varied and sometimes undiscovered history. Some of the history begs us to ask as many questions as it answers, but that is how we learn. The value of recording the facts and remembrances is important because future generations will have questions of their own, even if the question is about something as simple as a road sign.

Published 2009